“Few people will come right out and tell you that they belong to the Ku Klux Klan. It’s like saying you’re a Communist, you don’t like apple pie and moms or that you get a sadistic pleasure in kicking little children.”

-Journalist Stanley G. Robertson on interviewing a KKK supporter in the Valley, 1966.

By 1960s, the scary white people of the San Fernando Valley were making themselves known. Growing more aggressive and vocal in their intimidation of Valley-interested Black families, some Valley residents were steadfastly pro-segregation. Local groups like the Fair Housing Council of the San Fernando Valley (FHC/SFV) and others were continuing to challenge this racism with strategically coordinated efforts and gaining literal ground: Black families were coming little by little. But with every win these groups secured, the threats and noise grew more intense. And then, the Ku Klux Klan arrived in the Valley.

By the fall of 1961, the FHC/SFV reportedly had “two major breakthroughs” in their fair housing efforts, according to the Los Angeles Sentinel1. The organization both referred and secured housing for two respective Black families to two separate neighborhoods in the Valley: Northridge and Canoga Park. Consider how big a deal it was that two Black families buying property was literally headlining news (the story was enthusiastically reported the day the sales took place.) In the face of rampant housing discrimination, what was apparently working for the FHC/SFV was a strong referral system; a lot of this was dependent on members spotting homes for sale in their own neighborhoods and then proactively approaching the owners to list the homes with the FHC/SFV.

Down through history, there is no greater inciter of bigoted rage than minority cohorts experiencing joy and security.

A 1963 newsletter2 to council members offers a script of what Valley residents should say should they see a home for sale in their area. This tactic was directly presented to members as what they could do, as individuals, to enforce and preserve California’s fair housing law:

“‘Good morning! I notice your home is for sale! You wouldn’t like to list it with the Fair Housing Council, would you?’ Not quite right, but — how would you say it? That was a major question before the recent FHC workshop attended by some forty persons. A sample of the role-playing technique used at the workshop, wherein home owners encountered FHC clearing-house representatives seeking listings, will be re-enacted at the meeting.” (Emphasis theirs.)

By the following year, the council had launched a “Valley-wide” Emergency Campaign to Preserve the Rumford Fair Housing Law3, reportedly partnering with civil rights organizations and coordinating conferences with the San Fernando Valley Board of Realtors. Things were definitely moving.

More importantly, most Black Valley residents at the time were apparently pleased with their move. A 1965 report4 from a sociologist based in Reseda, and the UCLA sociology department, consisted of interviews with 104 “barrier breakers”—i.e. Black adults who moved to the “predominantly white communities of the San Fernando Valley.” What they found also made headlines:

“In response to the question, ‘If necessary, would you go through a move like this again?” all but eight said they would.

About half of those interviewed reported they were able to find a home in the Valley without any special difficulty which they attributed to their race. Fewer than one fourth experienced any opposition from their neighbors once they had moved in, and most of the incidents mentioned ‘might be described as petty rather than dangerous,’ the statement points out.”

While I’d appreciate a more thoughtful interrogation of the difference between “petty” and “dangerous” incidents from barrier-breaking Black families in white neighborhoods in the 1960s, I’ll accept the overall point: Black families were securing property and they were liking the Valley.

The backlash was as predictable as it was imminent.

This reported fact in and of itself must have been explosive to those hostile neighbors harassing one-fourth of study participants. Down through history, there is no greater inciter of bigoted rage than minority cohorts experiencing joy and security. This reality, communicated through newspapers and regional narratives, must have served as an incentive for bigger action5. The backlash was as predictable as it was imminent.

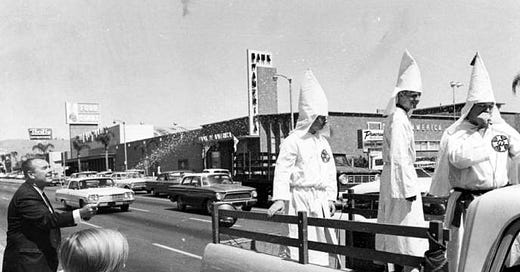

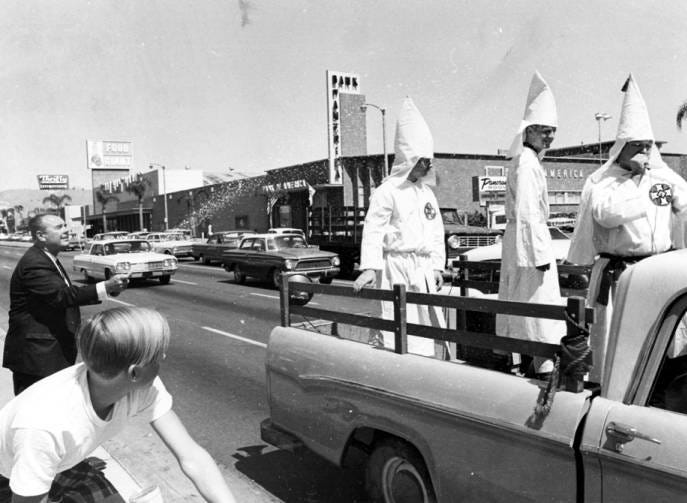

By 1966, the Ku Klux Klan made their presence known in the Valley with a parade in Panorama City. An archival photo of that day depicts three KKK members in robes and hoods standing in the bed of a Dodge pickup truck. According to the description, they are captured going south on Van Nuys Boulevard, north of Roscoe Boulevard. But a telling detail of resistance is captured just to the left of the frame: a white man in a suit to the left of the frame is spraying water on the Klan members. A young white boy on a bicycle looks on in suggested perplexity; he isn’t really sure what to make of this.

The dynamics captured appear almost mismatched. While the KKK is presenting themselves in all their racist granduer, the couple of people captured clearly aren’t impressed at all. There isn’t even a big crowd of support visible.

Stanley G. Robertson, who interviewed the unnamed white Valley woman about segregation in the previous Valley Girl, registered his disgust with the KKK presence in 1966. Covering a different KKK rally, he wrote about the misconception that the KKK was a strictly southern or midwestern organization, evoking a similar reframing to the pretty “educated” white lady who had racist views. He writes that the KKK was quite active in California until the hate group was deemed “illegal”6 sometime in the 1940s. But now, in the face of growing civil rights and diversified neighborhoods, they’re back. The tonality of Robertson’s narrative though suggests that they don’t belong in picturesque LA:

“But as I write this on a gorgeous post-card-type Los Angeles morning, only a few short miles from where I sit gazing out the window at the hybrid grapefruit-lemon tree which adorns my backyard, the hooded and despicable Knights of the Ku Klux Klan are planning to assemble and hold their first California rally in more than two decades!”

Robertson recounts eating lunch with a KKK supporter (!) in Burbank who identifies himself as “an executive with a large insurance firm”7 living in Granada Hills8. They make really awkward small talk about work, the executive throws around the n-word, and then asks Robertson what he thinks about integration. Robertson says flatly that he supports it. And then the KKK supporter says what he thinks:

“I think it does neither the black man nor the white man no good. It’s all part of the Communist plot to destroy the integrity of both races, to change America into a race of mongrels9, a country of people who are neither black nor white. Don’t you see that by destroying all of our values, all of our Individualism that the Communist can move right in and take over?”

“I don’t,” I said still not changing my facial expression. The red was beginning to spread up higher in his face, cutting deeply into the blemishes and thin traces of teenage acne which still held onto his jaws and cheeks.”10

So, that’s how that went.

For the Black families who braved this type of hatred, the cost to their families, marriages, and physical safety was great.

Next week: the first Black families in the Valley.

“Valley Homes Open Minus Race Labels.” Los Angeles Sentinel, 23 Nov. 1961, p. A4.

“Fair Housing Council of the San Fernando Valley.” 19 Nov. 1963. The Huntington Library. San Marino, California.

“Valley Group In Drive to Keep Fair Housing Bill.” Los Angeles Sentinel, 2 Jan. 1964, Los Angeles Times p. A3.

“Valley Housing ‘Pioneers’ Would Do It Again.” Los Angeles Sentinel, 11 Nov. 1965, Los Angeles Times p. B5.

Robertson confirms as much. He writes of the more visible KKK presence in Los Angeles: “It takes no expert to point out that this is a direct result of the stepped-up push in recent years by the Negro for his civil, social, and economic rights.”

This isn’t true. The KKK as an organization was not deemed illegal in California in the 1940s, but many of their intimidation tactics and threats faced increased legal challenges. The Shelley Vs. Kraemer Supreme Court case in 1948 also determined that the State would not uphold racial discrimination in property law, which impacted how the KKK often maintained all-white neighborhoods.

Robertson suspects the man is lying about his name, profession, and residence.

Granada Hills is a neighborhood in the Valley.

He’s talking about me.

Robertson, Stanley G. “Confrontation With a Bigot.” Los Angeles Sentinel, 6 Sept. 1962; Los Angeles Times pg. A7.