“Like, oh my god!

(Valley girl)

Like, totally!

(Valley girl)

Encino is, like, so bitchin'

(Valley girl)

There's, like, the Galleria

(Valley girl)

And, like

All these, like, really great shoe stores”

—“Valley Girl,” Frank Zappa featuring Moon Unit Zappa, 1982

It was the popular culture of the 1980s that first told the world who the Valley Girl was. The most enduring trademarks of the Valley Girl1— the insatiable shopping, the “like” staccato, the bleached blonde hair — much of this perception was exported through the music, films, and TV aesthetics of Regan-era America. The economy, particularly for white Americans, was booming. And the Valley Girl? She was buying lots of stuff.

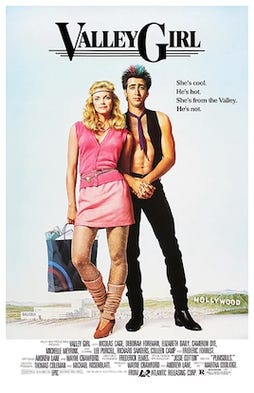

Movies like Valley Girl (1983) and characters like Julie Brown, the host of a weekly MTV show called Just Say Julie (1989), led by self-identified Valley Girls, were positioned as both engrossing but somewhat of a cultural oddity. Not quite cool but desperately trying to be, it was her perceived way of speaking that was most distinctive. And the broader American culture loved it. The 1982 Frank Zappa song “Valley Girl” featuring his then 14-year-old daughter Moon Unit Zappa mimicking the “Vals” accent, became the only Top 40 hit of his entire career and was nominated for a Grammy.

In a 1982 Los Angeles Times article marking the song’s sweeping popularity, Moon said that her father often called her “his little Valley Girl”2 and that he always had plans to write a song about her and her friends. She is quoted as describing not just the signature way of Valley Girl speak, but also the signature dress – “a ruffled blouse” with no bra, “a headband,” and “gold-leaf earrings.” A representative of Frank Zappa’s record company confirmed that unlike Zappa’s other songs, “Valley Girl” was not only getting tons of radio play, but that it was essentially “selling the album.”

Los Angeles Times staff writer David Frenznick notes:

“Valley Girl” clearly has more than local appeal. The song is captivating listeners as far as Chicago, New York and places where most residents never heard of Encino or the Galleria shopping complex, which is mentioned in the song as a favorite Valley Girl hangout.

Perhaps it is because every city has a “Valley,” a place where the nouveau riche settle down to middle-class bliss. Where children enjoy material comforts their parents never had—enough money to buy designer jeans, get their toenails manicured and purchase memberships in expensive figure salons.”

This assessment of the Valley Girl as synonymous with the middle-class suburbs and “material comforts” was echoed elsewhere. These early examples laid the groundwork for what would end up being an enduring truism: the Valley Girl was always white.

The opening scenes of the Valley Girl 3movie, a modern take on Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet starring Nicholas Cage and Deborah Foreman, introduce us to the title character through a montage of young white4 girls shopping. We arrive via a long drifting shot over the Santa Monica mountains by way of the Hollywood sign, communicating to us the proximity to a more recognizable Los Angeles (and maintaining the important suburban element). We first hear the characters speak in the food court of a mall, which directly transitions to a scene of a bunch of Valley Girls at the beach. The Valley Girl loop would be memorialized as going from the mall to the beach. She has no other destinations. The messaging of leisure, endless consumption, and the birth of a “lifestyle” is consistent and direct: when the Valley Girl is not shopping, she is lounging. She doesn’t labor or “work” in the economically-sanctioned sense of that term. She buys. She consumes. And that is how you identify her.

These early examples laid the groundwork for what would end up being an enduring truism: the Valley Girl was always white.

But as aggressively middle-class and white-bred as the Valley Girl may be, she’s never been exactly aspirational. From the beginning of her pop culture origins, there’s always been something deeply unsophisticated, mockable, and silly about the Valley Girl. Audiences are supposed to make fun of—and look down on—her.

Comedian, singer, and actress Julie Brown, a valley girl5 herself, played this up in her weekly MTV show, Just Say Julie, where she introduced music videos. In a 1990 Los Angeles Times piece detailing her screenwriting, entitled “Valley Girl Is Just One Shade of Julie Brown,” the reporter notes that Brown knows her “ditsy caricature of an empty-headed Valley girl” is over the top. That seems to be the point. The set of her half-hour show is reportedly “set in her tacky condo,” further characterizing the Valley Girl aesthetic for viewers.

“When certain Valley women dress up, they always look like they have too much of everything-too many layers, too many colors, too much jewelry and too much lip gloss."

This wasn’t just a choice by MTV. The cultural consensus, even beyond hyperbole, was that Valley Girls (and valley women) were just….too much. Even in real life. In 1985, a mother of two who was living the San Fernando Valley, told the Los Angeles Times that, “When certain Valley women dress up, they always look like they have too much of everything – too many layers, too many colors, too much jewelry and too much lip gloss." (She was reportedly from Michigan.) She says, "I call it the overglossed look."

Lee Cass, a vice president and fashion director of a department store chain, interpreted the maximalist trademark of the Valley Girl slightly differently: “The Valley look can be summed up in three words in my opinion. Lots of lace, layers and chutzpah. That means nerve."

But the notion that the Valley Girl was “too much of everything” didn’t begin and end with her. The judgement mirrored a broader assessment of the San Fernando Valley as a place of fundamental 1980s excess.

Even those who tried not to operate within this gender stereotype ultimately did have these assessments of the Valley. When the director of Valley Girl, Martha Coolidge, was interviewed about the film in 1983 she made a point to say to the Los Angeles Times, “I hope Valley kids like it…I don’t mean to caricature them or put them down.” But the reporter, Jayne Kamin, detects otherwise, ultimately picking up on a searing critique:

“The Valley does, however, take a beating. It’s depicted as a den of indulgence; rich, spoiled kids running rampant at the mall with Mommy’s credit cards. There are immaculately landscaped suburban backyards, the sterility, insulation, and arrogance and narrowness of a life style…”

It’s here that the disdain for the Valley Girl lives; somewhere between having disposable income and being woefully cringeworthy. She was the embodiment of a space defined by overconsumption.

She was the embodiment of a space defined by overconsumption.

This broader cultural reaction has important historical context beyond the Valley. Bigger shifts were happening in the United States, specifically around money and consumption. After two recessions, job growth was exploding. Over the entire decade, the working-age population would grow by 21.5 million people, many of which were women entering the workforce. Most of this growth would be attributed to what economists called the “services-producing industry,” so retail, finance, real estate, insurance — white collar, bougie jobs with a desk and reports (think shoulder pads and an assistant.) All of a sudden, middle-class Americans were very, very busy with their Very Important Jobs and needed everything on the go. A September 1990 Monthly Labor Review notes:

“The combination of greater spending power and less free time left its mark on retail and trade. Stores that sold products aimed at saving time and work and stores that offered service and convenience were among the most successful retail establishments during the 1980s. Fast food and carryout restaurants, as well as restaurants delivering food to the home, helped to meet the growing need for meals on the run. Eating and drinking places of all types headed the list of industries that added the most jobs in the 1980s…Mail-order catalog sales also benefited from the inability of busy consumers to find time to shop at stores. Other rushed consumers started using personal shoppers who preselected requested items, a new service offered by many department stores to facilitate many purchases in short time.”

And in tandem with more and more Americans being busier was the expectation to suddenly have a variety of personalized electronics, a rainbow of fancy items that had never been standard to any American household. These included things like Walkmans, VCRs, video camcorders, personal computers, and cable-ready TV sets. The prevalence of these electronics produced another industry entirely: stores that rented or sold movies or tapes as well as the electronic equipment. Monthly Labor Review observes, “The fastest growing segment of retail trade was radio, television, and music stores, which increased employment by 71 percent over the decade and added 110,000 jobs.”

Suddenly, the average middle-class American had a ton more stuff than the previous generation, and yet always sought out more. To encapsulate this era, I often think of Michael Douglas’s iconic monologue in the 1987 film Wall Street, espousing “greed is good.” At the same time, so many experiences for Americans were becoming increasingly engineered around buying: the shopping mall, the video store, the “eating and drinking places.” A constant figure at these establishments was the young, thin, white woman holding shopping bags, looking “overglossed,” and talking loudly about what she was buying next.

For the 1980s, the arrival of the Valley Girl represented a moment of pause; a questioning of what was actually happening in the culture.

The mockery of the Valley Girl ultimately distilled a distinct uneasiness with shifting economical realities, especially for young people (and namely young white women). She is not only the manifestation of a place that is overtly sanitized and commercially shaped, but also representative of a time where decadence, indulgence, and overabundance were quickly becoming emblems of the era.

For the 1980s, the arrival of the Valley Girl represented a moment of pause; a questioning of what was actually happening in the culture.

What were MTV, massive shopping malls, and suburban surplus doing to young people? But more importantly, what kind of young white women and girls was it producing?

Predictably, misogyny had theories. In 1982, local valley girls told the Los Angeles Times exactly what Zappa’s “Valley Girl” had brought into their life: harassment. As genuine valley girls, the association was not great, even then:

“‘It’s degrading, disgusting, and horrible,’ said a Birmingham High School sophomore as her three friends nodded in agreement. ‘There are girls like that in Beverly Hills and Brentwood, too. It gives the stereotype that all Valley teen-agers are trendy little airheads (empty headed).”

The teen-agers complained the song has made it difficult for them to wear a miniskirt, or go shopping or even walk down the street without being the target of verbal harassment.

‘You can’t do anything without some guy leaning out of his car window or something and yelling, ‘There’s a typical Val’,” another girl said, ‘I mean, it was funny at first, but now it’s getting stupid.”

This type of geographical harassment brought a new dimension of self-consciousness and shame to the experience of being young and female in Los Angeles. Originally, the Valley Girl was depicted as liking her suburban bubble (I defer to Moon’s monologue). According to the 1980s narrative of the Valley Girl, she liked the commercial suburbanism for which she was known.

In the Valley Girl movie, this sentiment is affirmed. Cage’s character, Randy, a Hollywood punk, hints as much when meeting Valley Girl Julie, played by Foreman. He tells her that people in the Valley are “programmed,” implying that there is something inauthentic about where she is from. Wholesomely sweet in a punk club in Hollywood, Julie tells him, “the Valley is real enough for me,” once again asserting that the Valley Girl likes her natural habitat of the Galleria and food courts. She also nervously eyes Black pedestrians from the car when arriving in Hollywood, suggesting she doesn’t just see Black people walking around where she lives.

But as the Valley Girl stereotype left the 1980s, she would no longer be portrayed as liking her Valley bubble. The Galleria and the shoe stores would now operate as a source of embarrassment. Too provincial. As the gender trope moved into the 1990s and 2000s, her goals shifted: the Valley Girl didn’t want to be in the Valley anymore.

Next week: the Valley’s sordid reputation.

Uppercase “Valley Girl” to indicate the manufactured caricature.

This interview reportedly takes place in Studio City (solidly in the Valley). But I’ve seen reporting elsewhere to indicate that Moon grew up in Laurel Canyon with her father (not the Valley.) Either way, it seems like she spent a lot of time in the Valley as a young girl.

Frank Zappa reportedly sued the filmmakers of the Valley Girl movie to prevent them from using “Valley Girl” as the title. He was unsuccessful.

It’s important to note that that these young women are coded as white. They could very well be passing.

Lowercase “valley girl” to indicate a female-identified or pangender individual who happens to be from or inhabits the San Fernando Valley.