“Are you asking me how I vote or what I believe?”

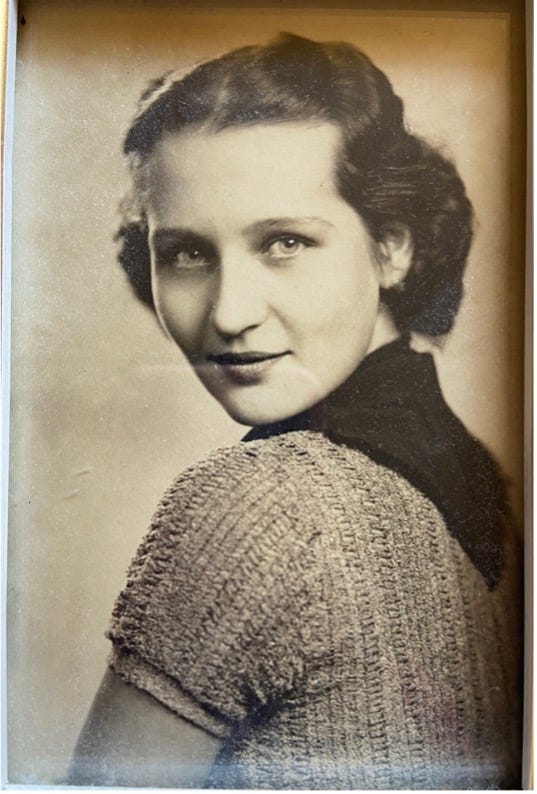

-my grandmother, Kathleen Beck, when I asked her if she was pro-choice, circa 2001.

The Valley promised twenty-first century, affordable living to some, but what the community often delivered was prejudice. From the inside, the sinister promises of the Valley were a push-pull of NAACP action, fair housing initiatives, and good old-fashioned bigotry to control and cement its newfound image. The white side of my family ran up against this all the time, especially in the early years.

My paternal grandparents moved to the San Fernando Valley in 1945. About five or so years later, my grandfather bought a sloping plot of land in a new “developing” suburb with my grandmother’s approval after she saw Clark Gable1 zoom by on a motorcycle. She told me she had been sitting on a tree stump when she saw his signature profile, my grandfather chatting with the realtor. According to family lore, she quickly ran over to the suited men discussing square footage and interjected “We’ll take it! We’ll take it!” I imagine it very well might have been the most glamorous thing to happen to her in months.

At the time that she saw Gable go by, my grandmother had been living in a rented house in North Hollywood. “In the space of a year,” I remember her telling me 50 years later, “I suddenly had a husband, a house, a yard, and a baby.” Even when I was little, I always picked up on the intonations of upheaval here; like she had gotten dizzy one day in New York City and when she got her head back together, she was suddenly living thousands of miles away from both the home she came from and the home she forged for herself as a young woman. And now, she was tasked with making a third.

“In the space of a year,” I remember her telling me 50 years later, “I suddenly had a husband, a house, a yard, and a baby.”

Not long before, she had been writing a radio show in New York City, walking up and down Madison Avenue where white-collar men happily grabbed her and then managed to look offended when she turned around sharply; all blue eyes and high cheekbones that could narrow at the exact same time. She had been the first in her family to go to college, a divine opportunity of birth order, in which her father decided the youngest girl in the family could pursue higher education. This put her on a wildly different path than that of her siblings and especially her sisters who had stayed in small-town Illinois, promptly married, and produced children like good Irish-German Catholics. And yet their “kid sister” Kathleen had not only received an expensive interlude, but then went even further to a metropolitan city with something that we would now call career ambitions. It didn’t really make sense.

And yet other facets easily did. Like when my grandmother reached the age of 25 and still wasn’t married, it was assumed across the family that she never would. “What man would want you?” is the voice I can hear coming over the telephone as if it were me answering the call. “Obviously, you’re too old to have children.”2 She proved them wrong by the next year, delivering my father in a Los Angeles hospital after my grandfather, whom she had married a tidy nine months before, was offered a job as a news director at CBS News.

When she told her family about the opportunity, she characterized them as nodding and listening intently to the logistics. They supported the move and thought it was a lovely idea to have a family member living out in California. And when she finished and there was a lull between breaths and speech and her mother and sisters asked, “and when will you come back?”

By most standards of the time, she was a good, white 1950s housewife. Except if you actually talked to her.

This had been the hardest part, she told me later in the living room of the house I live in now. The house my grandparents would build on that sloping plot of land after Clark Gable rode by. The house my wife would later restore as I uncovered my grandmother’s Catholic junior high report cards. (High marks in everything.) I see it very cinematically. Her standing newly pregnant in her mother’s kitchen and explaining gently that they weren’t coming back. That was the whole idea.

Shortly after my grandparents moved into their forever Valley home, they made an effort to meet people. Granted, there weren’t that many immediately around. The neighboring lots stayed empty for years, my father spending most of his boyhood riding bikes over them and back again. There were sheep farms not too far down the street and my father was promptly enrolled into private Catholic school, a walk he would do by himself for years in an itchy uniform. I see my grandfather going off to work every day over the hill and coming back with colleagues from the newsroom: other reporters, producers, or editors—people my grandmother entertained with cocktail hours and laborious, multi-course dinners. By most standards of the time, she was a good, white 1950s housewife. Except if you actually talked to her.

After neighbors saw Black people coming in and out of my family’s home, rumors circulated that my grandparents were Communists.

She attended exactly one meeting at a local Valley ladies society club but very quickly learned she didn’t have much in common with the “Valley Girls Dine Out” crowd. In doing an audit of my grandmother’s values, it’s easy to see why: she thought it was criminal that professional athletes made more money than teachers; she personally thought that abortion was wrong but didn’t think it should be illegal or inaccessible to those who needed it; even though she was a stay-at-home mother and full-time wife, she made all the financial decisions in the household. As a new valley girl3, my grandmother’s values were too progressive for her 1950s suburban community.

I think of my grandparents hearing about this place with cheap land and going to see the Valley for themselves. It seemed like such an easy financial choice to make, especially for a young family. But the aggressive normalcy would turn out to be a lot for my family to navigate. And challenge.

My grandmother’s unconventional marital dynamic, in addition to her political opinions and the company she and my grandfather kept, raised suspicions among other Valley residents who had wholesale bought into the homogeneity promised to them. After neighbors saw Black people coming in and out of my family’s home, rumors circulated that my grandparents were Communists. Not too long after that, a local mother in my neighborhood asked my white father to chaperone her daughter’s date with a boy in the neighborhood. Why? Because the boy was Jewish.

The Valley Girl4 was constructed to both signal and maintain suburban values but more importantly, to affirm that the Valley was not Los Angeles city proper. On this side of the hill, these streets don’t have Blacks, Jews, Communists, or many other boogey men from 1950s America who are rumored to be crawling the city en mass. On this side of the Santa Monica Mountains, the Valley has nice, modest, white daughters and wives who keep house and go to church and host dinner parties around their fancy new washing machines.

The Valley Girl was positioned as the quaint, new antithesis of Los Angeles. Until she wasn’t.

Next week: the Valley Girl gone wild.

This cannot be confirmed but Clark Gable Estates is nearby, so the scenario is entirely plausible.

My grandmother told me that her brother said this to her.

Lowercase “valley girl” to indicate a female-identified or pangender individual who happens to be from or inhabits the San Fernando Valley.

Uppercase “Valley Girl” to indicate the manufactured caricature.