My house lies on Mulholland and as I press the gate opener, I look out over the Valley and watch the beginning of another day, my fifth day back, and then I pull into the circular driveway and park my car next to my mother’s, which is parked next to a Ferrari that I don’t recognize.

-Bret Easton Ellis, Less Than Zero (1985)

While the Valley Girl1 of the 1980s was busy shopping in the suburbs, something more nefarious was happening in the background. Amidst her copious trips to the beach and shopping sprees, the Valley was getting a reputation which, to me, has always gendered the geographical space as female. The San Fernando Valley was becoming the plaything of namely rich, white boys and the aftermath of their proclivities. And for that, the Valley was deemed “trashy.”

This reputation was explored amply in the popular culture of the time. In 1985, author Bret Easton Ellis2, then only 21 years old, published his first book entitled Less Than Zero, to much acclaim. If you haven’t read it, you should, particularly if you’re interested in this era of Los Angeles/Valley lore. The novel, which then became a film in 1987, depicts a bunch of young LA-based characters ranging from 12 to 18 years old doing drugs like cocaine and heroin, engaging in sex work, committing sexual violence, and burning through their parents’ unsupervised wealth without consequence (except, perhaps, their mental health). Their exploits span a lot of Los Angeles, including the Valley – Studio City, Tarzana, Encino, Woodland Hills; but also well beyond it – Mulholland Drive, Beverly Hills, Melrose, Santa Monica, and Palm Springs.

When famed book critic Michiko Kakutani reviewed Less Than Zero for The New York Times Book Review, she characterized it as “one of the most disturbing novels I've read in a long time.”3 Most of what she found chilling was the eerie detachment and pessimism of young people against the backdrop of sex, drugs, and really, really nice clothes. These LA brats weren’t excited about really anything. Despite all that they had materially, they did not seem to experience joy. The summer of the book’s release, Kakutani summarized the book in a way that cannot be said any more succinctly:

The narrator, Clay, and his friends - who have names like Rip, Blair, Kim, Cliff, Trent and Alana - all drive BMW's and Porsches, hang out at the Polo Lounge and Spago, and spend their trust funds on designer clothing, porno films and, of course, liquor and drugs. None of them, so far as the reader can tell, has any ambitions, aspirations, or interest in the world at large. And their philosophy, if they have any at all, represents a particularly nasty combination of EST and Machiavelli: ‘If you want something, you have the right to take it. If you want to do something, you have the right to do it.'‘

The parents of these kids are mostly successful Hollywood types - cliches of all the worst aspects of L.A., they have capped teeth, lifted faces and vacant souls. They consult astrologers, gulp down pills, swig white wine, and carry on sordid little affairs - thoroughly oblivious, as Mr. Ellis makes clear, to their children's unraveling lives.

Kakutani had many criticisms of Less Than Zero as a work of fiction. She found the hyper-distilled style of the book ultimately at odds with her assessment of a “full-fledged novel” (some chapters are only a page and none are numbered). She compared the narrative style to “fast-paced, video-like clips” which she says produced “predictable scenes involving sex, drugs and rock-and-roll.” To which I say, Los Angeles is predictable.

There is a dark accuracy with which Ellis captures white elite Los Angeles, specifically with suburban exteriors of “good” families. The complete detachment between “friends,” the casual sexual violence, the truncated way in which characters speak to one another about absolutely nothing, the chasm between parents and their children set across excess; these are precise and perennial themes. Everyone in Less Than Zero has no connection to anyone, and that seems to ultimately be what troubles them. Clay and his friends and family are utterly siloed, floating across freeways and canyons just because there isn’t anything else to do. They are emotionally and spiritually vacant, another classic talking point about the people who live here.

I have never been a rich, drug-addled teenager, but I have driven the 405 as a very lonely young person in a halter top and wondered what the hell I was doing here. The emotional realities of these characters are not unfamiliar to me, specifically as a valley girl4. There is something sensorially disorienting about this stretch of desert; the inability to hold onto or connect with others is something I’ve received very long, unpunctuated text messages about over the course of my life. The desperation of people in my phone and on my heart who come here but, for factors they can’t quite express, end up awash in melancholy. Some say it’s the constant sun or the traffic or the heat or car culture or the cost of living or work. It very well might be. But when I hear them describe the listless feeling that can find them suddenly when the cars move slow, I know exactly what they mean.

I have driven the 405 as a very lonely young person in a halter top and wondered what the hell I was doing here.

The geographical unmooring that Ellis encapsulated, however trite to a surveyor of fiction, is tonally truthful to some versions of Los Angeles and Valley life. The drug abuse and empty sexuality of the book are almost secondary. It’s how these young people emotionally navigate Los Angeles that is the key landscape of the book. And other classic American writers have said the same thing, in much of the same way.

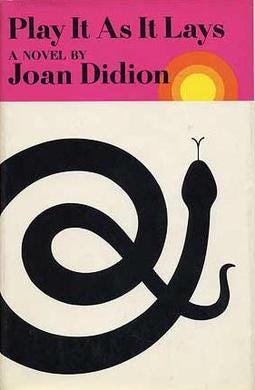

Ellis has said that Joan Didion is one of his major influences, and nowhere else does this show more distinctly than in my favorite Didion text, Play It As It Lays, published in 1970, and, later, adapted into a film in 1972.

Once again, the Valley is depicted as part of the druggy, empty-sex filth of Los Angeles, but also as having a unique shame and seediness to the overall story.

The Valley is, after all, where Didion’s main character, fictional actress Maria Wyeth, goes to get her DL abortion unbeknownst to her friends and industry people. “Under the red T,”5 the unnamed voice on the phone tells her when navigating off the freeway. She gets her abortion in a suburban house in Encino. Her doctor is characterized by her director husband as "the only man in Los Angeles County who does clean work." The contrast is pretty stark: an actress who lives in Beverly Hills and gets her hair done at Saks has to go there to access an illegal abortion6. It’s that type of place; a hotbed of illegal abortion.

There are a lot of logistical factors7 to Maria making this appointment; she has to drive out to the Valley, leave her car, and then get into another car, with a man she has never met, who will then drive her to the Encino house. The exactness of the directions signifies that the multitude of women who have come before her – probably women coming from all around Los Angeles County – has required the creation of precise instructions. This is a word-of-mouth service.

The fancier, more elite people from over the hill spend much energy distinguishing themselves from the seedier Valley.

And yet, despite all the vacuous parties, “everybody’s sick arrangements,”8 and degrading phone calls with producers, it’s the house in Encino that seizes Maria the most. Scenes from her time getting her abortion in the Valley are the most visceral, felt by a main character who, much like the kids in Less Than Zero, doesn’t often feel much of anything. For all the time that Maria feels terrible, it’s her time in the Valley that makes her feel the worst. And considering her labyrinth of depression, that’s really saying something.

A template is set here. For glamorous Los Angeles people, the Valley is presented as a place that feels solidly unglamorous— a space outside the flattering sheen of Hollywood, both metaphorically but also literally. The fancier, more elite people from over the hill spend much energy distinguishing themselves from the seedier Valley. In both Less Than Zero and Play It As It Lays, the division between the San Fernando Valley and Los Angeles proper is overt. In Less Than Zero, there’s even a scene where Clay witnesses a young Valley Girl waitress being Valley-shamed by male customers from over the hill9:

“Oh, for Christ’s sake, can’t you add?”

“I think it’s right,” the waitress says, a little nervously. “Oh yeah, do you?” he sneers.

I get the feeling something bad’s going to happen, but the other one says, “Forget it,” and then, “Jesus, I hate the fucking Valley,” and he digs into his pocket and throws a ten on the table.

His friend gets up, belches, and mutters, “Fucking Valleyites,” loudly enough for her to hear. “Go spend the rest of it at the Galleria, or wherever the hell you go to,” and then they walk out of the restaurant and into the wind.

When the waitress comes to my table to take my order she seems really shaken up. “Pill-popping bastards. I been to other places outside the Valley and they aren’t all that great,” she tells me.10

Consistent with the 1980s caricature, the Valley Girl is assumed to be an idiot, incapable of adding a check correctly, but also without any awareness of the world outside the Valley. This division, and in particular, the snobbiness with which other LA denizens perceived Valley Girls, would set up another enduring dichotomy. The Valley Girl was the cheaper, less desirable step-sister to the girls and women of adjacent, chicer neighborhoods like Bel Air, Beverly Hills, Santa Monica, and West Hollywood.

No wonder she wanted out.

Next week: the Valley is slutty.

Uppercase “Valley Girl” to indicate the manufactured caricature.

Ellis grew up in the Valley in Sherman Oaks.

Kakutani , Michiko. “BOOKS OF THE TIMES; THE YOUNG AND UGLY.” The New York Times, 8 June 1985, p. 32.

Lowercase “valley girl” to indicate a female-identified or pangender individual who happens to be from or inhabits the San Fernando Valley.

Didion, Joan. Play It as It Lays: A Novel. Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1970. pg. 76.

Play It As It Lays was published three years before Roe vs. Wade was passed. By 1970, California state law had decriminalized abortion under very specific circumstances. Maria’s abortion is illegal.

As we are reliving again in a post-Roe vs. Wade country.

Didion, Joan. Play It as It Lays: A Novel. Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1970. pg. 48.

“Over the hill” is an expression I used to hear my grandmother use when referencing anything over the Santa Monica Mountains.

Ellis, Bret Easton. Less Than Zero. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2010. pg. 57.